Gwyneth Walker

For Braintree Composer Gwyneth Walker, The Commissions Keep On Coming

by Ruth Horowitz

Return to Gwyneth Walker Home Page

Return to Gwyneth Walker Music Catalog

Return to Gwyneth Walker Recordings Page

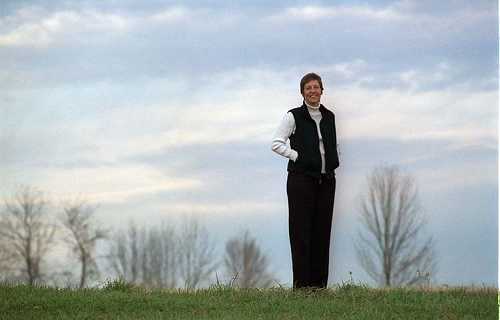

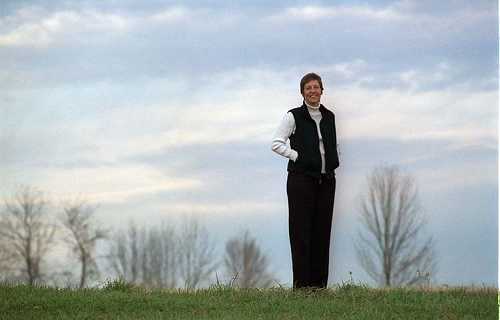

Plenty of people sing for their supper. Precious few bring home the bacon by composing - especially by composing the sort of music that doesn't sell toothpaste or embellish TV car chases. While most classical American composers support their writing habit with faculty positions or salaried spouses, fifty-two year-old Gwyneth Walker, who lives in Braintree, lets her songs, sonatas, overtures, concerti, and other musical works support her. "Not many people are exemplars for what she's been able to do," attests UVM music professor Jane Ambrose. "She's almost unique."

And almost as unique in her success. This year, Walker received the American Choral Directors Association's prestigious Raymond W. Brock Commission. This month, her "Symphony of Grace," a full-length symphony commissioned by six orchestras across the United States, premiers in San Francisco. On New Year's Eve, Florida music lovers will welcome the year 2000 with her "Millennium Celebration" for orchestra, chorus and school ensembles. And more works are in the works -- enough to keep the composer composing for the next two years, with new commissions coming in all the time, and performers

regularly performing her previously published works.

What makes Walker's music so sought-after? "Her music is very accessible to all different levels of sophistication," says Pamela Massey, who handles performance credits for ASCAP. "It's not so obscure and academic that regular folks can't enjoy it." Fellow composer Hilary Tann states, "Her great, great gift is in word setting. Gwyneth sees things in the words most of us wouldn't see. Her setting of ‘Clementine' is just a masterpiece."

Florida conductor Christopher Confessore compares Walker's instrumental style to that of Aaron Copland or Leonard Bernstein. But he's quick to add that it's neither imitative nor derivative. "It has a clean, open, classic American quality to it; a lot of energy and momentum."

The same might be said for Walker, herself. The composer is built tight and talks fast -- especially when the topic is her life-long love affair with her muse. In one of her earliest memories, she is a two year-old lying in her crib in her family home in New Canaan, Connecticut, and becoming conscious of music for the very first time. "My sister was taking piano lessons when she was in first grade," she recalls. "I was supposed to be falling asleep and I heard, directly under me, this *sound!* And it was so exciting that the next morning, when my sisters were in school, I climbed up on the piano and started making sounds every day. I got better at emulating what she had been playing, and then I started making up my own things."

As soon as she was able, Walker turned her developing art into a social activity. At six, she was already committing her compositions to paper and urging friends to play her creations on toy instruments.

By Junior High, she was arranging rock songs to be sung in harmony. As an undergraduate at Brown University, she earned her spending money writing arrangements for a singing group. Composing "has always been something I've done for other people, as well as for myself," Walker says. "How could you be writing something that somebody doesn't want? That's inconceivable."

At the Hartt School of Music, in Hartford, Connecticut, where Walker did her graduate work, she first encountered composers who wrote without specific performers in mind. Later, when she joined the faculty at the Oberlin College Conservatory, she found herself caught in the same insular routine as her colleagues -- correcting students' assignments and composing in a vacuum. "I really felt not myself," she confesses. "And so I left my teaching job."

Walking away from a successful academic job was a big move -- one Ambrose calls "terribly brave," Tann describes as "courageous." After making the move, in 1982, Walker spent a year pulling together a marketable catalogue of her works. At about his same time, she settled into the apartment she still rents on a 500-acre dairy farm on a road called, appropriately enough -- though not because of Walker -- Brainstorm Road.

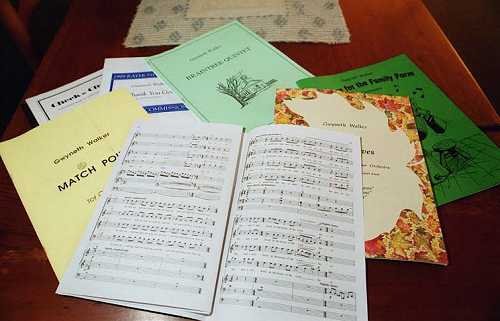

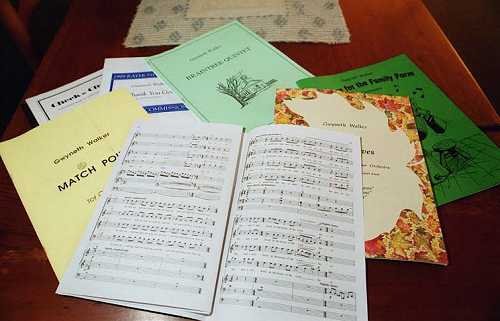

The composer's big break came in 1985, with "Match Point," an orchestral work inspired by Walker's love of tennis. The piece is designed to be conducted with a racket, which mimes the motions of a volley, a wind-up, and a smash.

The composer's career took off when Billie Jean King conducted the piece at Carnegie Hall. Walker still seems dazzled by her encounter with the tennis great. The racket King used for the performance hangs on her wall, along with displays devoted to other heroines, including artist Georgia O'Keefe, poet Lucille Clifton, governor Madeleine Kunin, and a rather somber, formal portrait of Walker's own Quaker ancestor.

With over 120 commissioned works under her belt, Walker takes a highly organized approach to her craft. Ask how a new composition begins, and she answers, "With a commission." Two years usually elapse between the signing of the contract and the delivery of the finished piece -- plenty of time to let ideas percolate, and to get to know the commissioner. "The more I talk to them, the more obvious it is what I should write," she explains. "The person and the music for whom you're writing -- it's all one." Once she actually starts composing, Walker begins with broad strokes, first describing -- in words -- the overall form and feel she's after, and then lining out measures to determine how the various parts of the piece will work together in time.

When that's done, Walker finally puts down notes. "I use a piano, and I sit at the desk, and I pace the floor," she says. Sometimes, she carries the music in her head as she walks up her road. "I hum through the entire movement. People who see me on my walks sometimes think that something's wrong, because I walk in the tempo of the piece, so if it's slow, I'll probably look like I'm about ninety-nine."

If the conceptional phase of composing is all-consuming, the actual execution can be tedious. "When you get it down, you have to put in the dynamics, the slurs, the tempos," Walker notes. "You have to tell the trombonist how to play that note: is it accented or not? Is it loud or soft? Does it grow from loud to soft? Is there a mute? These people don't know your ideas. You have to tell them absolutely everything."

In 1995, when Walker was working on a concerto commissioned by Susan Pickett, a violinist in Walla Walla, Washington, the composer frequently checked in with the performer. "She would send me the music, and I would play it for her over the telephone and comment if I found something awkward," Pickett remembers.

Walker makes a point of attending the final rehearsals and premiers. At these performances, she sometimes decides a piece still needs fine-tuning. Last winter, at the premier of "Appalachian Carols for Chorus and Brass Quintet," she realized that a certain French horn solo was too difficult for the average performer to play beautifully. "I heard this mess coming out of the horn," she confesses. "So I decided to rewrite it to make it possible for the trombone to also play it, because the French horn is a difficult instrument to play. You don't want someone struggling."

This winter, several ensembles will perform "Appalachian Carols." After hearing the performances, Walker will decide whether to publish the work as is, or revise further. "It's a lesson in discipline," she acknowledges. "I knew last Christmas time that this was a piece that had a real market value, and that if I didn't fix it up -- well, once it gets printed and everything, you're not going to go back. And if I don't like it at Christmas time," she adds, "I'll make more changes. If it's too hard to play, then it's not going to get played."

At another premier, Walker was surprised by the passion of her own writing. She'd set some May Swenson love poems to music, but didn't happen to hear them performed until much later, when a group of Randolph singers included them on their program. "A couple people stopped me in the Grand Union saying, ‘Oh, Gwyneth, we just *loved* these songs! They're so lush!'" Walker recalls. "And they kind of *looked* at me." Walker arrived at the concert and sat down, slipping off her winter parka. One piece, "Love Is a Rain of Diamonds," was supposed to sound like light fractioning off of diamonds, she says. "And it did! And when those women started singing it, and they had such romantic, sensuous voices, I was a little embarrassed. My parka that was just sort of sitting about me, and I just kind of was pulling it in, and I found my posture deteriorating so that I had almost slithered under the pew, because I was so embarrassed."

Selling enough music to make a living and still respecting your artistic self in the morning might seem like a hard act to pull off. But Walker seems perfectly comfortable with her dual purpose. She composes every day from nine until three, then switches from the art of making music to the business of making money. "To make a living at this is exhausting," she concedes, noting that she usually toils right up until dinner time, then plugs away into the evening. "I am busier now than when I was teaching. But the business and the creative side are very much intertwined." Knowing that someone is paying her to compose -- not from a grant, but out of their own pocket motivates her to do her best work. And making sure as many people as possible hear what she has to say through her music keeps Walker working. "You have an obligation to say the things that you uniquely can say," the composer believes. "I am best qualified to speak about the kind of life I live here. I like straightforward, sincere, God-revering, beautiful, humorous kinds of music that

can reach people from all walks of life."

The composer expresses her philosophy in her latest work, Symphony of Grace, a piece she describes as an acknowledgment of her faith. Her love for the natural beauty she sees out her window in Braintree infuses the first movement, which quotes the hymn, "For the Beauty of the Earth," with "waterfalls around it in the strings, and perhaps insects going by," the composer explains. In the second movement, "Companions Along The Journey," Walker uses the folk style she sang in college, and honors the friends who sang it with her. Her sense of humor drives the upbeat "Many Creatures" movement, which starts out

with a tango in a barn and ends with a predator portrayed by a slapstick -- a percussion instrument that slaps like snapping jaws. The symphony closes with a quiet, reflective passage called "The Spirit Within" -- Walker's musical expression of devotion.

According to Reverend Kathy Eddy, a Braintree neighbor and a fellow composer, almost all of Walker's music has this same "spiritual underpinning. It comes from her life as a Quaker and attending to the inner light that is God's presence," the minister explains. Belief is certainly a central element in Millennium Celebration, Walker's next major work. "We wanted something that had an uplifting inspirational message, something that was very broadly ecumenical but did not shy away from thanking God," explains Carol Hawkinson, head of the Bradenton, Florida group that commissioned the piece. The performance, which includes children's, community, church and high school choirs, a pop orchestra and a group of young string players, concludes with the audience joining in on the grand finale.

If Gwyneth Walker had a theme song, it could be the hymn they sing: "Let every instrument be tuned for praise," one verse proclaims. "Let all rejoice who have a voice to raise. And may God give us faith to sing always: Allelujah."

Photographs by Christian Wideawake courtesy The Rutland Herald

From the Vermont Magazine of the Rutland Herald, Rutland, Vermont, November 14, 1999. This article also appeared in Seven Days.